The world, especially Europeans that have respected the status quo and supported the EU and the Euro, breathed a collective sigh of relief after French voters rejected the latest surge in populist sentiment that has been sweeping across developed economies. The “pause” button can now be tapped. We can shift out of neutral and begin to roll again, or can we? Try as we might, politics cannot be separated from trading and investment strategies, but the recent distractions have allowed a few unsettling situations to go unnoticed by the analyst community at large. What lies ahead, and will the global economy begin to escalate in the ensuing months?

These questions never seem to go away. Doubt and uncertainty continue to plague our global markets, but volatility seems to be hibernating. It is May, the time when many investors close their positions, go off on holiday, and return in September, although the tide seems to be favoring August, if the last few years are any indication of changing sentiments. It is now nearly a decade after the Great Recession, yet economic growth in the developed world has been, for want of a better phrase, stuck in the mud. Fed forecasts for the U.S. economy are in the 1.8% to 2.0% ballpark, while Europe would be luck with half of that figure. China keeps plugging along around 6.5%, which continues to be a mystery, when demand from the West is so low.

What is going on behind the Chinese curtain? Are numbers to be believed, or are there unpleasant situations that are finally reaching a real breaking point? As much as we would like to believe that China is an isolated microcosm, we know in our heart of hearts that the majority of goods and credit are created in the Middle Kingdom. The world’s commodities and many of the developing markets about the planet depend upon the Chinese production machine. If it skips a beat, along with globally entwined logistic infrastructures, then be prepared for a few major bumps along the road. If global economic growth is to resume in a higher gear, then China is a major part of the answer.

Read more forex news and analyses

What are the current prospects for GDP growth and why are they so low?

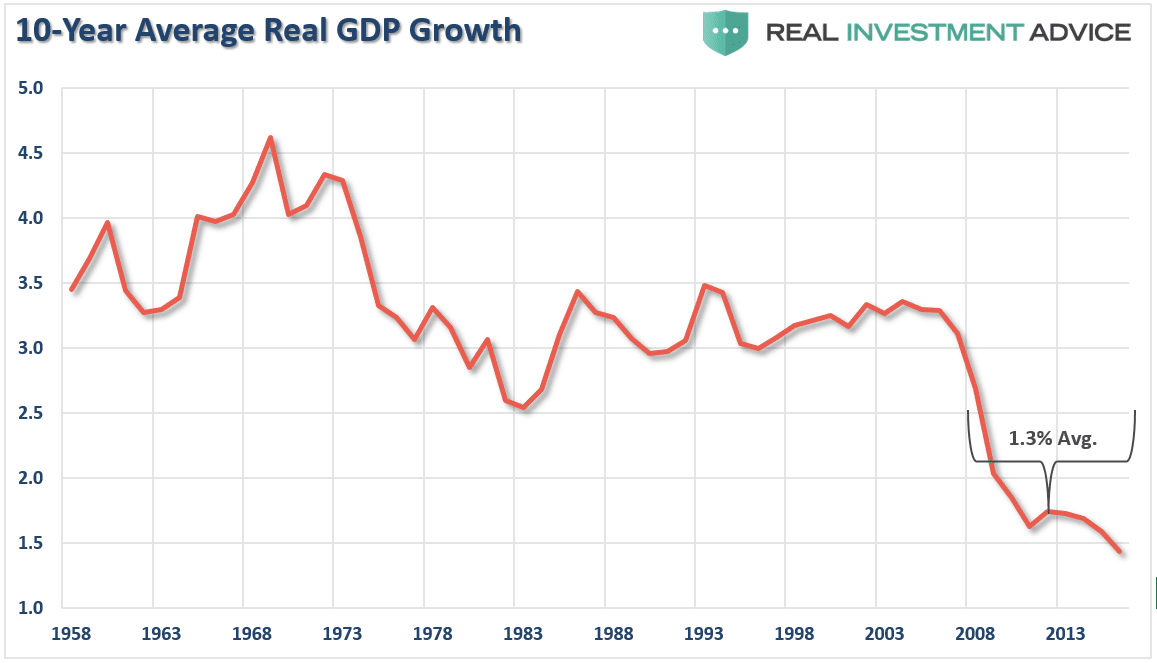

The past decade has been one of low economic growth expectations, regardless of the amount of central banking stimulus that has flooded the system with liquidity. The phrase most often heard of the current conundrum is that officials are merely “pushing on a wet noodle.” Various quantitative easing programs and near to negative interest rates have not jumpstarted the economy, as in the past. Real GDP growth data in the U.S. for the past ten years has averaged a mere 1.3%, in sharp contrast to an average of 3.1% for the thirty years leading up to the recent financial crisis.

If the United States economy is to pull the rest of the world back to prosperous times, the current narrative on the street, then something has got to change. Promises by the Trump administration of tax reform, increased infrastructure and military spending, and reductions across the board in costly regulations have pumped up expectations and equity values, but, at some point, actions must match up with the rhetoric or a sudden tailspin in valuations could launch the dreaded “risk-off” event that everyone continues to worry about.

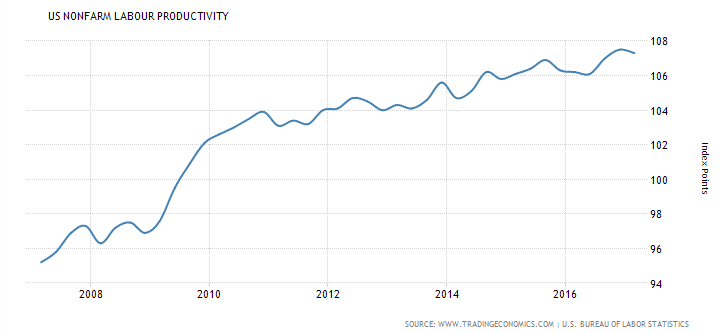

Political intransigence is one thing, but basic economic logic is another. The U.S. economy is consumer driven, by nearly 70% by most estimates. If GDP growth is to accelerate, more money must reach the hands of consumers, and they in turn must be willing to spend it on goods and services, not put it away in savings or pay down debt. In order for businesses to make profits and have the funds to pay workers more, there has to be a material increase in productivity to warrant such actions. If anything, measures for productivity are sometimes suspect due to the influx of low-priced items from abroad, but the following chart from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics tells the story:

The issue then becomes what is happening with the labor force – is it growing, as in the past, or slowing? By the Fed’s own pronouncements, we are currently at “full employment.” Growth in the labor force has been forecasted to be 0.5%, not the stellar figure of 1.5% for the three decades leading up to 2007. Slower growth in the labor force translates to slower growth in the economy, but if we are at full employment as the Fed maintains, then more stimulus will surely lead to inflation, higher interest rates, and higher government deficits, each factor weighing heavy on growth dynamics. The only way out, it would seem, would be to achieve a dramatic increase in productivity.

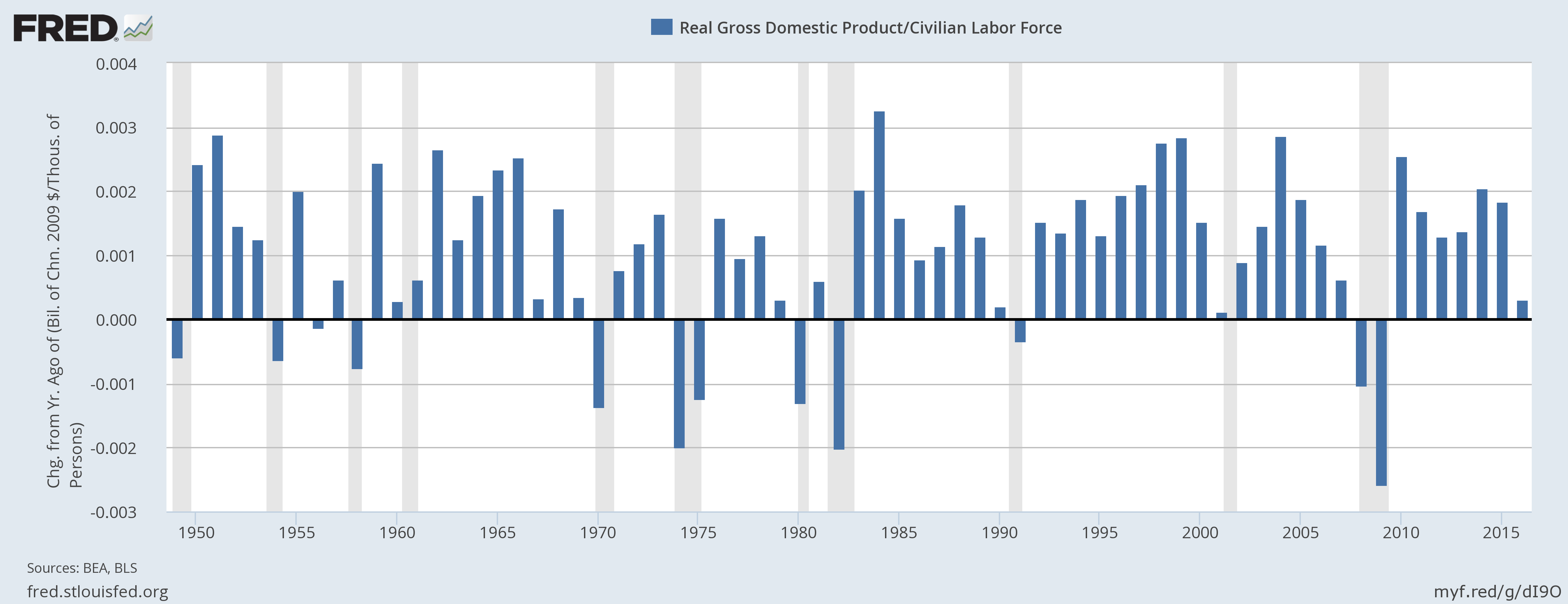

Boosting productivity is not completely out of the question, but political machinations to stimulate the economy will only borrow from future growth estimates. There is no “free lunch”, so to speak, when it comes to government spending. Eventually, more taxes will take away from funds in the system that would ordinarily increase domestic product data. There is one more statistic that is troubling at the moment, and that has to do with the amount of GDP generated divided by the size of the labor force.

It is easy to look over this chart and notice that a dramatic drop in the “blue” bars immediately precedes a recessionary downturn. Is this one chart signaling that a recession may be imminent? Is this that one “killer” chart that every analyst has been looking for? Before we duck and run, we must remember that current times are different. The global economy has been twisted into an enormous knot, due to central banking policy, which even the bankers claim will take many years to unravel. In other words, current distortions make comparisons to past history suspect by most measures.

What should growth expectations be for the future? Can government officials really impact the situation for the long term? As one analyst put it, “We honestly can’t expect growth to be much more than where it is. Never mind slow growth now. Unless we somehow achieve those elusive productivity gains, which are arguably the only path to a better standard of living, the culmination of all of these factors conspires to be a drag on economic growth later.”

What is really happening in China? Are we in for a wake-up call anytime soon?

Transparency is not a word that one would use to describe China or the economic statistics that emanate from Chinese officials. The general consensus is that the government is so concerned about its image that any distribution of data about anything has to be spun to match the prevailing storyline of how things should be. For this reason, there is literally a second band of external analysts with banks, brokerage houses, and hedge funds that attempt to construct their best guesses of what the real numbers actually are.

One of the major issues deals with the Chinese banking structure. Massive government banks follow guidelines to the letter of announced law, but there is an entire “shadow” industry of quasi-banks, acting as either agents of the national institutions or on their own entirely. The Brookings Institute described it this way: “Shadow banks are financial firms that perform similar functions and assume similar risks to banks. Being outside the formal banking sector generally means they lack a strong safety net, such as publicly guaranteed deposit insurance or lender of last resort facilities from central banks, and operate with a different, and usually lesser, level of regulatory oversight. These characteristics increase the risks for financial stability, which is the main reason there is a focus on shadow banks today.”

The issue gets cloudier when one remembers that “shadow” banks in the developed world nearly crashed during the financial crisis. Brookings continues: “The rapid development of China’s shadow banking sector since 2010 has attracted a great amount of commentary both inside and outside the country. Haunted by the severe crisis in the US financial system in 2008, which was caused in part by the previously unsuspected fragility of a large network of non-bank financial activities, many analysts wonder if China might be headed for a similar meltdown. The concern is especially acute given China’s very rapid rate of credit creation since 2010 and the lack of transparency in much off balance sheet or non-bank activity.”

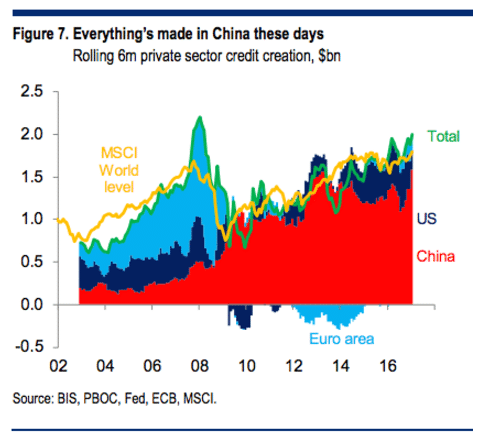

The concern gets even cloudier still when one sees how much credit China has created on a global comparative basis, nearly 80%, as per the following diagram:

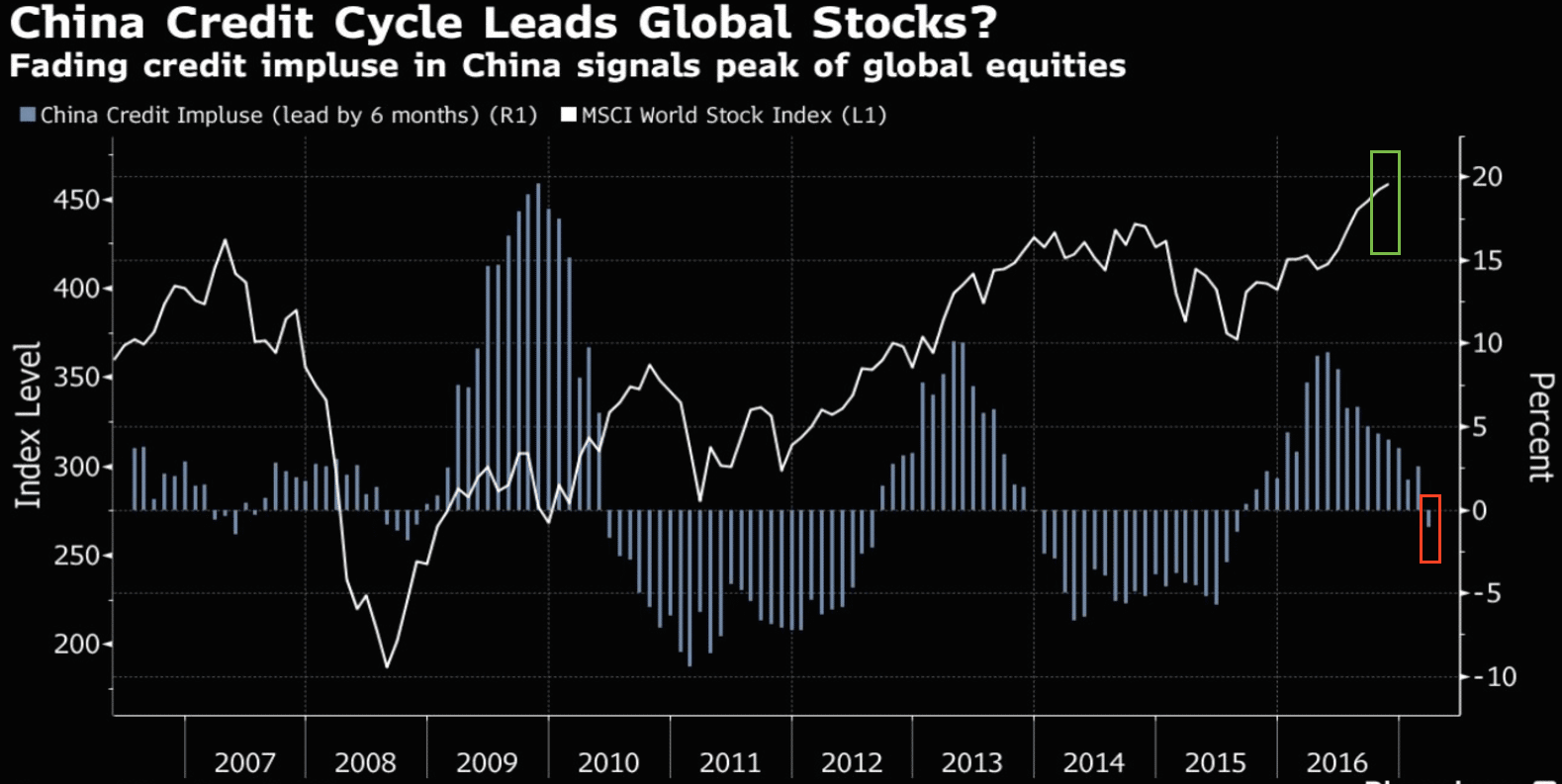

In the recent past, both the U.S. and Europe have actually gone in reverse. What will happen if a similar situation develops in China? Per another analyst, “If that system you see in the chart goes into reverse, there is no global credit impulse. Private sector credit creation flatlines across the globe. Given that, it certainly shouldn’t come as a surprise to you that credit growth in China is a leading indicator for equities.”

Once again, economists have researched historical trends and prepared the disturbing correlation that is self evident from the following chart:

As in the previous Real GDP – Labor Force comparison, are we looking at a leading indicator of what may transpire in the months to come? Negative responses of the China Credit Impulse do seem to precede a negative downturn in global equity valuations. First quarter data for China were positive on several fronts, leading to optimistic forecasts for the next eighteen months. If you look behind these favorable results, Leland Miller at China Beige Book is not that impressed: “We’re not just seeing another quarter of cheap credit in China. We were seeing some of the loosest conditions we’ve ever seen in the history of the China Beige Book survey.”

Shadow banking is known for inflating asset bubbles and causing carnage where it is least expected. Contagion and spillovers to the commodities market are real possibilities, if and when non-performing loans “in the shadows” collapse the system. Miller adds: “The idea that (the Chinese) are going to stabilize at 6.5 GDP growth, or whatever number they’re making up these days, or they’re going to accelerate like some economic analysis I’ve seen has suggested lately, that’s just not going to happen.”

Concluding Remarks

The Economic Union may be alive and well for now, but the fickle spotlight of fate has focused once more on China and its shadow banking industry. Many believe that it is stretched beyond prudent limits and will soon snap. Time will tell, but be prepared!

Between 74-89% of CFD traders lose

Between 74-89% of CFD traders lose  Your capital is at risk

Your capital is at risk  Your capital is at risk

Your capital is at risk  Your capital is at risk

Your capital is at risk