The economic skies are looking gloomy again over the European continent, and poor Mario Draghi, our inimitable chairman of the ECB, has already used just about every phrase that exists in his central banking playbook, until he overtly described the present situation as “overcast”. The EU economy has once again failed to deliver, although it did stumble over weaker than expected data, as risks became more prominent on all fronts. Raising interest rates is out of the question anytime soon, and to top every off, Italy also slid into recession.

Wherever Mr. Draghi looks, it is, well, overcast. Germany, the bulwark of the EU economy, has posted its slowest growth in five years. Brexit just keeps dragging on, one week on, the next week off, uncertainty the main theme. The slowdown in China has always been worrisome, as are the current trade disputes with the U.S., which prompted him to point a finger at the lack of sustained stimulus from Trump’s tax package. Lastly, inflation dropped, as if it ever was headed in the right direction, due to declining oil prices.

As dismal as the outlook may appear, Mr. Draghi does have a few good things that he can reference, even if his magical hat has run out of rabbits. The central bank has finally discontinued quantitative easing. It stopped making open market purchases, primarily government bonds, last month. The ECB’s balance sheet is still bloated to the tune of $3 trillion and change, but QE is over. Its benchmark interest rate has remained at zero for four years, although the rate paid to banks for their overnight deposits is still negative.

Read more forex news

In the midst of what the BBC has termed a “territory of unconventional policy”, Draghi has been word-smithing on the side. Instead of using the more generic phrase of “normalization of central bank policy”, when the ECB speaks to raising interest rates, it will now call the process “forward guidance”. In fact, the word from the bank is that it “expects the key ECB interest rates to remain at their present levels at least through the summer of 2019, and in any case for as long as necessary, until inflation approaches the desired target of at or just below 2 percent.

With forward guidance out of the way, Mario proceeded to hint that changing interest rates might be a bit further off than others might think, which prompted the press to ask the obvious question: “When?” Financial markets had been speculating that the ECB would commence raising its rate sometime in 2019. Mario’s response was completely in character, when he said that markets “have understood our reaction function”. Reporters could only shake their collective heads at this rather arcane twist of technical phrasing. Mario had done it again, a new phrase, which everyone interpreted to mean that rate hikes would be somewhere past 2019, if ever.

How has the Euro reacted to these events and what lies ahead in Q1?

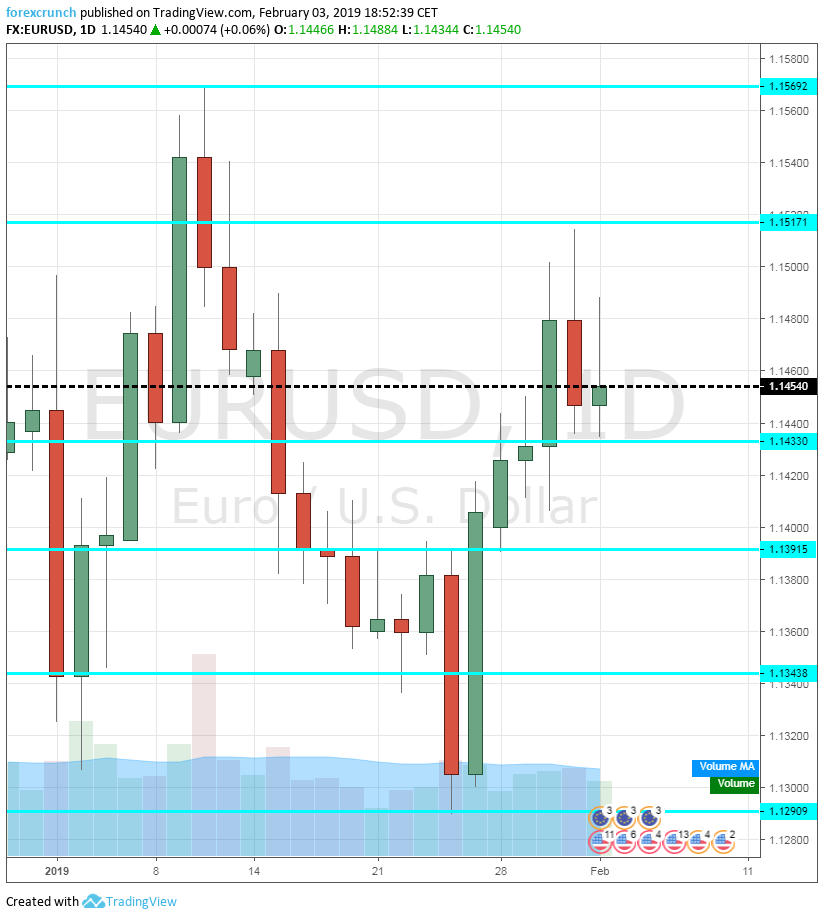

Surprisingly enough, the Euro has shown respectable resilience in the face of gathering storm clouds. For January, it has been locked within tight boundaries, rarely straying from its 1.135 to 1.155 trading range. It presently sits at 1.145 – see the chart below:

The trend has been slightly positive and ascending growth, if you accept that a bottom was established back in November of 1.125. Over the last three months, that low point has ticked up by one percentage point, and Bloomberg’s consensus prediction for the end of Quarter One stands at 1.16, a tad higher still than a month ago, when the herd was forecasting 1.15. GDP growth has been anything but stellar, i.e., 0.4% for the first half of 2018 and 0.2% for the latter half. Contraction is the name of the game, which had necessitated a soothing refrain from Draghi in the past. He “signaled that the bank will act if evidence of a prolonged slowdown in momentum continued to mount”.

The Euro’s path has been gradual, almost mirroring the general narrative that claims that the Almighty Dollar must decline over time. Since the EUR makes up nearly two thirds of the index, it would seem that it has to outperform the greenback on some statistic, even though bank forex department expectations do not claim it to be necessary. The USD has bounced similarly about a 97.0 value, but dovish-ness on the part of the Fed may be its downfall. Analysts concede, however, that a dovish Fed may not be enough.

Across the channel, Sterling has been the top performer against its competition for January, appreciating 3.2% versus the USD and 3.5% against the EUR. The Pound has had a nice run for six weeks, based on an increasing belief that a hard Brexit would be delayed. Opinions, however, are mixed on how this entire scenario will play out. The ruling government is acting as if a delay will focus efforts, as the March 31 deadline approaches. Here are a few of the prevailing thought themes:

- “The underlying strategy appears to be to allow the looming deadline to focus attention on what is widely seen as a cliff edge to be avoided. A second referendum is possible and may be gaining support. On the one hand, it is returning the question to people for more instruction of their intent. On the other hand, if Remains win, the Leaves will be inconsolable.”

- “Regardless, we believe the costs for a hard Brexit are too high for both parties, even if the EU is playing a different game than the U.K. For now, the market seems to agree that some agreement will be reached, avoiding the hard Brexit scenario.”

- “Since the UK’s 2016 referendum, Eurozone shipments to the single currency bloc’s second-biggest export market have stagnated. If the clouds clear in the coming months, with a no-deal Brexit avoided, then risk premiums will diminish, sterling will rally and Eurozone exports to the UK are likely to pick up. For now, however, the outlook on this front remains highly uncertain.”

Once again, we have a “territory of unconventional policy”. Sterling improves in anticipation of a Brexit reversal or delay, yet every analyst out there, using game theory or basic logic, posits that a total reversal will bring on Armageddon. In any event, uncertainty is no friend in the trade arena. Exports from the EU are down to the UK, to the U.S., and most of all, to China.

As the debate rages regarding the EU’s economic fate, the idea of the Euro moving to parity with the U.S. Dollar has been resurrected again. In the past, the mere mention of this hypothesis would stimulate buying demand for the Euro, almost as if every central bank with sizable Euro reserves panicked and quickly acted to supply much needed support. Times now are different. The argument now starts with the basic question: What will the EU do if hit with a broad-based recession?

Italy is there already. France and Germany may be closer than one would like to think. Interest rates are at zero. The balance sheet is full up. The conclusion then follows: “The long-term scenario for the Euro is overwhelmingly bearish. If the EU will require more stimulus than the US in the next downturn, and the ECB has never left the zero-bound, we may start to see some more monetary experiments that will more than likely push the Euro lower, not higher.”

Just how bad are the economic statistics that support a dismal EU outlook?

No matter where you look, there seems to be a continuous theme of foreboding, as if negativity has been building up in the dark and is now about to be unleashed to see the light of day. A few tidbits:

- The growth rate for the Eurozone was 0.2 percent for the fourth quarter of 2018, which “puts growth at its lowest levels in more than four years;”

- Italy is in recession, after successive negative growth quarters of –0.1 percent and –0.2 percent;

- Germany had a 0.2% contraction in Q3 2018—and only 0.5% growth the quarter before. Fundamentals worsened, too;

- France is not doing well either, and general weakness applies almost everywhere;

- Labor productivity growth has been almost non-existent over the past decade;

- The issuance of junk bonds has gone “parabolic”, a condition generally followed by a recession;

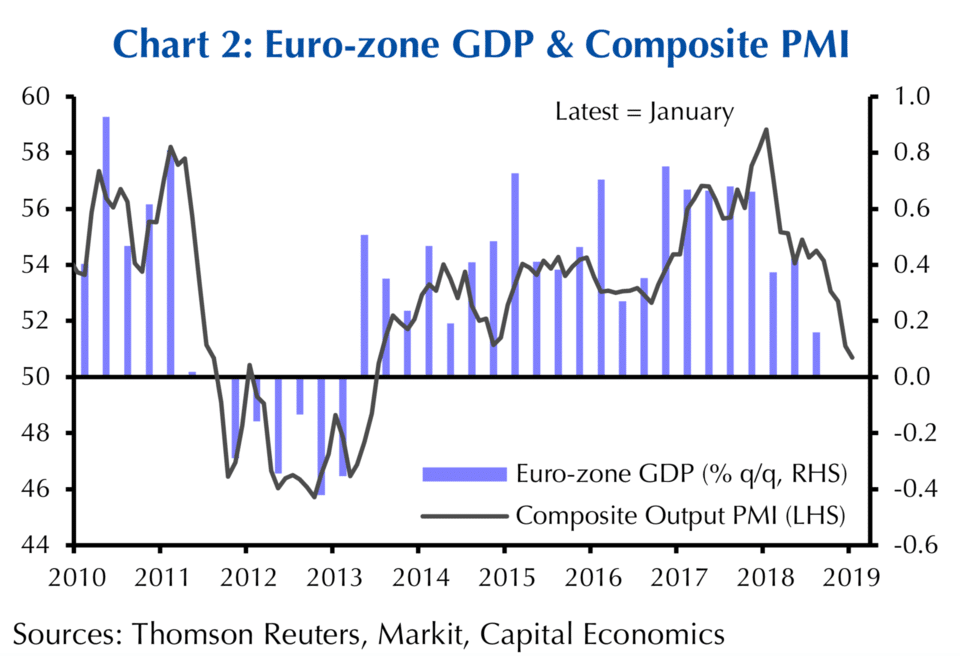

- “The Eurozone Composite Purchasing Managers’ Index, a measure of sentiment in all types of companies, flatlined, pretty much as it did before the recessions of 2009 and 2012.”

The latter item causes the greatest concern when looking forward, because the sentiment held by most economists is that, “The Eurozone economy needs solid growth in its core manufacturing sector to perform at its best, and at the moment, it seems like growth here is falling off a cliff, almost that is.” The following chart shows anything but prerequisite performance in the core manufacturing area:

Germany has always been the bellwether of manufacturing activity in the EU, but it, too, is slipping. Structural issues may be building up in the background: “The policy debates Germany needs concern chronic weaknesses that would be laid bare by a recession. Those include a failure to cultivate entrepreneurial startups, especially in service industries; a stubbornly unreformed banking system, made vulnerable by decades of political meddling in managements and years of profit-sapping ultra low interest rates; and a tax code that kills incentives and investments. That’s for starters.”

But Italy is already in recession. Could we have another Greece situation at hand? One analyst is very concerned: “The renewed recession in Italy might trigger uncertainty and vulnerability within the euro zone. The weakness of the Italian economy puts back at center stage the huge public debt of the country, which is persistently a cause of economic and financial trouble for both Rome and Brussels. Even if the size of the Italian economy should prevent a debt crisis as deep as the one Greece experienced, the accumulated debt and the inability of governments to reduce it makes it impossible for the euro zone to conclusively put to rest the risk of a crisis which it might not survive.”

Concluding Remarks

Will the EU find its way out of its current economic predicament? One analyst thinks not: “As usual, Europe will just kick the can down the road again in trying to return the Eurozone to faster economic growth. The real questions will not be addressed, just as the real questions surrounding the Brexit struggle will not be addressed.”

With Europe, it seems as much as things change, they always stay the same.

Between 74-89% of CFD traders lose

Between 74-89% of CFD traders lose  Your capital is at risk

Your capital is at risk  Your capital is at risk

Your capital is at risk  Your capital is at risk

Your capital is at risk